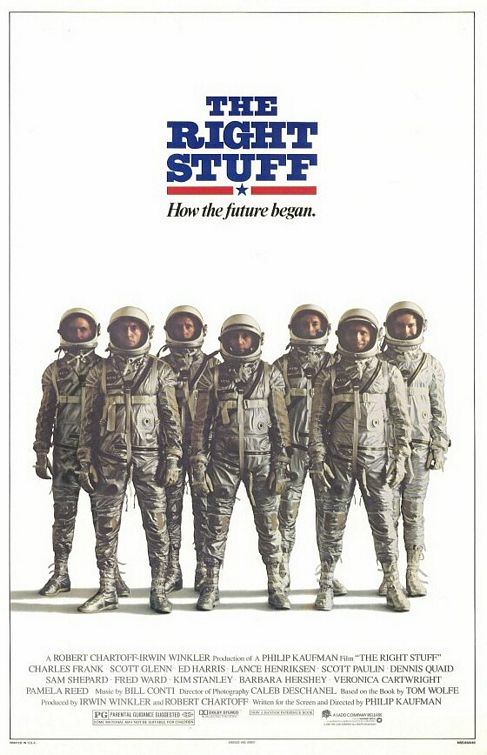

Let’s talk about The Right Stuff (1983), Philip Kaufman’s classic movie about test pilots (most prominently the famous Chuck Yeager) and astronauts (the original group of the Mercury space program) and about the first steps of the United States’ space program. It’s a favorite movie of mine which I’ve enjoyed watching periodically since I’d discovered it during my film-science courses at the university.

Part adventure, part comedy, part satire and part drama, it’s not an easy film to pinpoint. From the moment it starts, with a dramatic voice-over talking about the ‘demon in the sky’ (the sound barrier), it feels both larger than life, and smaller in scope than most hollywood productions. And throughout its entire runtime you’re pushed around from broad comedy to touching drama to spitting satire, sometimes within the space of 15 minutes.

The message, which evolves from that format, still is poignant in that it celebrates the broad vision of those early pioneers and relishes in the feeling of being witness to a sort of coming-of-age of mankind, at least as far as technology is concerned, while at the same time quite critically examines the weirdly inconsequential actual benefits of the whole space program. At times it all just feels as an exercise in upstaging the Russians or even more basic, as a young boy’s ambition to continuously being ‘on top’, to be ‘the fastest’, no matter how short-lived and ultimately futile those aspirations might be.

Compared to more straight-laced movies about the space program like Apollo 13 (1995), or the HBO series From the Earth to the Moon (1998), The Right Stuff feels like a story told by an author who actually has something interesting to say. It’s quirky, symbolic and suggestive, yet constantly entertaining.

So what about it’s cinematography? As this still is One Shot and not a ‘film review’ blog per se. Well, there’s a lot to say about it. Though not constantly a visual tour-de-force, The Right Stuff is clearly filmed by an interesting cinematographer, namely Caleb Deschanel. All throughout the film there are interesting flourishes and visual tricks of storytelling that give the movie depth. Like framing an aircraft to suggest it being a kind of monster, the film-noir style he uses to decorate the local bar of the test pilots, or the weird and surreal tunnel-vision he shows from a pilots’ perspective every time a pilot takes a giant leap forward in the evolution of the space program (which seems like a clear nod to 2001: a Space Odyssey’s black monolith). At times it literally feels like an artistic indie-film in its use of visual metaphors and suggestive themes.

Most interesting, however, is when Deschanel succeeds in capturing the larger theme of the film and integrating it into a single shot.This is, after all ‘One’ Shot! And that larger theme, to me, is the duality of its subject. The child-like naivety of that generation of pioneers and the darker, more dangerous reality surrounding the space program. The innocence and the critical combined.

And Deschanel has a shot in this film that perfectly conveys this duality in one single image. So striking and effective has he done it that I imagine if I just show it below without any further explanation, it would suffice. But it doesn’t feel like an easy, or cheap shot to me. It feels like an extremely well thought-out moment that fully uses the frame of the movie also in its three dimensional space. Here it is:

So this is an image that contains four different layers, all combined to express the theme of the entire movie. Starting from the closest layer we have the silhouette of Gordon Cooper’s wife Trudy standing in front of a window looking out at the desert in front of her. Second in line we have solitary barbecue which links directly to a related shot which follows this one. Thirdly we have the two daughters standing by the fence, playing around with their dolls and lastly we have the looming smoke of a nearby plane crash, signifying another casualty in the world of the test pilots.

So let’s start with Trudy Cooper. The first thing I was reminded of was the famous shot of John Wayne in the Searchers (1956). In that film there is an image of Wayne standing in a doorway, framed as a silhouette against the background of the open desert. There, it suggested that the inside-world of Wayne’s family is unreachable to him and he is bound to the solitary desert he walks towards in the final moments. Standing on the threshold of the familial house, he cannot pass and must retreat.

In this shot, Trudy is similarly standing on a threshold. Only it is an inverse of the one from The Searchers. Here she is standing inside of the familial world (together with the other wives inside) and she is detached from the outside world of the test pilots (all the men are standing in the garden, off-camera, enjoying a barbecue). In a world filled with John Waynes, it’s the wives who are detached and secluded and ‘cannot pass’.

Secondly, the barbecue of course relates to the following shot of the men joking around the other barbecue, laughing over a burnt sausage, which kind of relates to the burnt test pilot out in the distance. Notice that the barbecue in the frame is placed just below the smoke in the background, further emphasizing the metaphorical relation between the two.

Also worth noting is that Deschanel chooses to connect this image to the barbecuing men off-camera, but chooses to not show then within this frame. This is important because it further separates then from the familial. By placing the men in a different space than their wives, and not framing within one shot, it is made even clearer that these two groups live in separate spaces.

Then thirdly the girls. They are of course the symbolic innocence, as well as the essence of the familial life. Having them play against the backdrop of a tragedy is both poignant and horrific. It is poignant because it creates such a strong contrast between the ending of a life and the beginning of one (death versus children) and also horrific in the eyes of Trudy because she sees that the children are witnessing the tragedy and don’t seem to be fazed by it as much as herself. Which makes it that much more difficult for her; not only is she a witness to the tragedies, her children are also witnesses and their playfulness might suggest they will get used to it, which I believe ultimately motivates Trudy to leave her husband (temporarily).

And then ultimately, there is the smoke, the thing that triggers all the drama in front of it. So within one frame Deschanel places a tragedy and has three different groups of characters as a witness to it. And through his choice of composition all three grounds relate to the tragedy in a different way. The kids react in naivety, the men witness by ‘not witnessing’ it (or choosing to ignore it?), and the wife witnesses it as a detached bystander.

This, to me, is perfect storytelling. Visually, silently, through one effective composition, one of the main themes of the movie is demonstrated and the dynamics and relationships between three groups of characters are captured within that frame. You can’t get more effective in your storytelling than this…